by Pete Skirbunt

Harvest festivals are as old as civilization itself, but our Thanksgiving is much more than an annual festival. It is a national day of expressing thanks, according to every individual’s personal beliefs.

There were many “thanksgivings” in the early days of American colonization, when life and travel were so difficult that people were always giving thanks for safe journeys, favorable weather and good crops. Spanish colonists held such feasts in Texas in the 1500s, as did English colonists in Virginia from the 1600s.

The thanksgiving we commemorate every November, however, was the one held by the Pilgrims of Plymouth, Mass., in 1621. Although it definitely wasn’t the “first” thanksgiving in the New World, it holds a special place in American tradition because of its association with the ideals of religious freedom, self-reliance and the mutual friendship of settlers and natives.

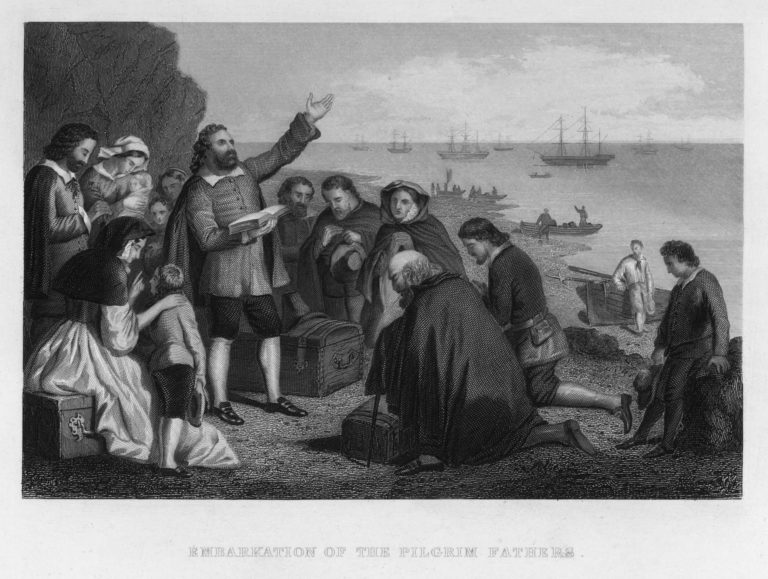

The Pilgrims — a name not actually applied to them until 170 years later — were 102 people who sailed from England on the ship Mayflower in September 1620.

Of these, only 35 were actually seeking religious freedom. They were “Separatists” from the Church of England. The others, called “Strangers,” simply wanted to leave England for a variety of reasons and start life over in America.

For 12 years, the Separatists had lived in Holland, where the Dutch tolerated religious differences. But these Englishmen didn’t want to desert their heritage, customs or language. They decided to go to America — to Virginia, specifically. Establishing a colony there would allow them to remain English. If they went elsewhere, to Dutch colonies, for instance, they would have had to renounce their English citizenship.

King James I, eager to be rid of them, gave them permission to establish a colony, so long as they remained loyal and didn’t cause him trouble. The Virginia Company of London agreed to let them settle in “Virginia,” which at that time extended north to modern New Jersey. Merchants calling themselves “Adventurers” agreed to finance the expedition in return for seven years of shared profits from whatever the colonists were able to produce and send back.

In August 1620, the first Separatists sailed with 67 “Strangers” on the Mayflower and a second ship, the Speedwell. After the Speedwell twice sprang leaks and forced returns to port, everyone crammed aboard the 90-foot-long Mayflower and left the Speedwell behind.

Aboard ship, the voyagers ate bread, biscuits, pudding, cheese, crackers, and dried meats and fruits. Instead of water, they brought barrels of beer — a standard practice in the days before refrigeration, because beer remained potable longer than water.

The 3,000-mile voyage took 66 days, meaning the ship averaged just two miles per hour. On the way, one baby was born, and his parents named him “Oceanus.” Two people died, and the ship nearly sank in a storm.

They finally arrived, badly off course, at Cape Cod in November. This was a problem. The season and location made planting impossible, and winter hunting would be difficult. Since their agreement with the Adventurers specified they would settle “in Virginia,” they ordered the captain to head south. The wind was contrary and the coast was dangerous, however, so they turned back and found safe harbor at Cape Cod.

It was then the Strangers announced that because they hadn’t been delivered to Virginia, they weren’t bound by the contract and would take orders from no one! In fact, the Separatists feared all their agreements with the company, the Strangers and King James were completely useless. But they knew if there was division, there was little hope in anyone surviving.

Before going ashore, the travelers drew up the “Mayflower Compact.” One of the most significant documents in U.S. history, the statement was the first by any settlers that they intended to abide by the will of the majority. The 41 adult males who signed the document agreed they and their families would obey laws set up for the general good. They also set the precedent that only adult males would have a voice in government — a precedent followed until 1920, exactly 300 years in the future.

In December, a scouting party went ashore, and tradition says they first set foot upon the stone known today as “Plymouth Rock.” This may or may not be true, but the rock is so large that they probably at least used it as a landmark when rowing ashore.

The men in this first group ashore feared a possible confrontation with unfriendly Indians, but soon they discovered the local Indians were all dead of smallpox. They took this as divine providence and assumed God had cleared their way by killing off the natives.

They established their colony with little but faith and courage and named it “Plymouth” in honor of their final port of departure. The Mayflower remained offshore, but most of its provisions were needed for its crew’s return voyage.

Meanwhile, the settlers couldn’t plant crops, and they didn’t have enough supplies to last until spring. They’d lived in cities while in Holland, so they didn’t know how to fish or hunt. In their first month, they caught exactly one fish and shot no game at all. For awhile, it seemed they’d go down in history as the world’s most inept hunters and fishermen.

They suffered from cold, starvation and disease, and half of them were dead by spring. The survivors were in danger of suffering the same fate without much delay.

“Do you have beer?”

But everything changed in the spring, when a lone Indian walked into the settlement and said, in English:

“Welcome, English. I am Samoset. Do you have beer?”

The Pilgrims were astonished. Of all the places in America they could have come ashore, they’d been found by a friendly Indian who somehow spoke their language — and knew about beer. Once again, they were sure this was a sign of God’s personal intervention.

Samoset explained he’d learned English — and the fact that ships routinely carried beer — from having had contact with English fishing vessels. Unfortunately, one of the vessels had apparently also brought smallpox, which wiped out some of the local tribes. Samoset had survived.

Soon, he introduced the Pilgrims to other Indians, including Squanto, the only living member of the Patuxet tribe. Squanto spoke even better English than Samoset and said he’d been shanghaied by an English ship and taken to England, where he found work in London as a “living curiosity” and one-man carnival side show. Eventually, other fishermen took him back home so he could show them the best fishing spots. Upon his return, he discovered smallpox had wiped out his tribe during his absence. Later, the Wampanoags adopted him.

Now more than ever, the Pilgrims believed God had guided them to this place of friendly, English-speaking natives. According to their view, God let Squanto be kidnapped so he would miss the smallpox epidemic, learn English and arrive at Plymouth just in time to save them.

The Pilgrims also befriended the Wampanoag chieftain, Massasoit, and his personal ambassador, Hobomok. The tribe taught them to catch fish, lobsters and eels; to harvest clams and oysters; to plant corn and other vegetables; to fertilize by placing a small fish into the ground with each seedling; and to trap and hunt game.

The settlers eventually became good enough marksmen to provide fresh game. They also had a good autumn harvest, including 20 acres of corn.

Meanwhile the Mayflower returned to England, and two other ships arrived. The first brought no supplies, but did deliver more men and some mail, including a nasty letter from the Adventurers, complaining that they had sent no marketable products back with the Mayflower. The second brought more settlers and, fortunately, lots of provisions. This was a good reason to celebrate, so in October 1621, the settlement and 91 Native Americans held a thanksgiving feast.

This meal inspired much of our traditional holiday fare. The food included geese, corn bread, pudding, eels, lobsters, clam stew, oysters, corn, squash, potatoes, yams, cranberries, and pumpkin pies. The Indians contributed five deer, and the main course was venison. Turkey was a side dish, no doubt because the birds then weren’t domesticated, but wild, wily and not easily hunted — so few would have ended up on the table.

The settlers gave thanks to God and the Indians for helping them survive. The celebration lasted several days, during which there were sports, contests, entertainment and speeches of goodwill. Everyone agreed to make it an annual event, provided there was anything to be thankful for.

They signed a treaty and enjoyed harmony for 50 years. Unfortunately for the Wampanoags, arriving settlers brought European diseases that killed off the tribe by 1671.

Years after the first celebration, Massachusetts began observing Thanksgiving annually. Other Northeast colonies had harvest festivals, and by 1700, the holidays merged throughout New England.

In 1789, George Washington proclaimed a national day of thanks for the successful establishment of the Constitutional government. Ben Franklin, drawing on the tradition of the “Pilgrim Fathers” having eaten turkey, declared domesticated turkey should be the official entree. Franklin also lobbied to have the tough, smart wild turkey named the national symbol, but people didn’t buy it — probably because no one wanted a national bird that was regularly made into a meal.

As the nation grew, the Thanksgiving tradition spread westward from New England.

Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a harvest thanksgiving during the Civil War. Many states adopted the practice after the war as a kind of national healing process. In 1941, Congress established the fourth Thursday of the month as the national Thanksgiving holiday.

Thanksgiving’s traditional symbols include the cornucopia, the horn of plenty. Recent innovations, including parades opening the Christmas shopping season and televised football games, now seem as traditional as the meal itself!

Still, Thanksgiving remains a day with religious and patriotic overtones, commemorated with special services by all faiths, with its main emphasis upon the gathering of family and friends. This is the essence of the way it began, and we’ve successfully preserved it for nearly 400 years.

So, with all the modern distractions going on around you, I hope you can still find time to share with your family at least part of the story about the “first” Thanksgiving at Plymouth, and help them observe, if only for a few minutes, the spirit of the holiday as it was originally intended.

About the author: Pete Skirbunt is the historian of the Defense Commissary Agency, Fort Lee, Virginia. This article was originally published by the American Forces Press Service.