There is a history of racial inequality in America and out of this the hunger for African Americans to be able to equally express their citizenship rights took a nationally tangible shape. Sixty years before Black Lives Matter, there was the civil rights movement.

For people just coming of age, it might seem from current events that life has never been more arduous for people of color — with the exception of slavery. Whether you live in the United States or elsewhere, reports about how badly African Americans are treated throughout the U.S. dominate the news cycle. Stories involving police officers using people of color as target practice are all too common. So, too, are instances of white people calling cops on people guilty of nothing more than breathing, as a tactic of harassment and intimidation.

MORE: Meaningful ways to celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day at any age

In both instances described above, more often than not, cops and the “outraged” privileged aren’t even verbally admonished, let alone prosecuted for their crimes. Black people and other people of color individuals pay a high cost for this unjust behavior and are questioned about why they’re loitering in spaces white people have decided are reserved for themselves. Furthermore, people of color are routinely humiliated, arrested or, worse, killed.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) reports that while African Americans comprise just 13 percent of the country’s population, they make up between 40 and 50 percent of the 6.8 million people incarcerated in the nation’s jails and prisons. Despite the population disparity, people of color are incarcerated at five times the rate of caucasians.

As disturbing as this reality is for African Americans, there has been an overall improvement in the quality of life for people of color. This fact may be difficult for many to fathom — you may wonder, an improvement from what?

Well, imagine a world where, in addition to the incarceration and police brutality rates described above, you had to contend with laws that were created for the sole purpose of controlling every aspect of everyday life. You couldn’t rent an apartment in certain areas. You couldn’t send your children to schools where the education was better — those were reserved for white people. White-only public restrooms were clean and well-maintained. The ones for you? Dirty and in inconvenient locations. Imagine having an entirely separate set of laws applying only to you, simply because of the color of your skin. Go back less than 100 years, and this nightmare world was the reality for millions of black people.

MORE: 5 ways to celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day

The civil rights movement (1954–1968)

The civil rights movement began as a dignified, principled, non-violent response to everyday manifestations of oppression against people of color. The commitment to non-violence and legal reform that defined the early civil rights movement was a deliberate choice, one that even the most ambitious of reformers in 1950s America believed was necessary to bring lasting change and authentic achievement.

America’s Cold War paranoia over the so-called communist boogeyman gave opponents of social change a convenient weapon to use against those who dreamed of something better, and advocates for civil rights knew that in that climate, campaigns for change couldn’t expect to succeed if they challenged ideological pillars like patriotism, Christianity and an opposition to radicalism.

Integrated public schools

The Supreme Court had just ruled in favor of integration in 1954 in the landmark case known as Brown v. Board of Education. The monumental ruling — declaring school segregation unconstitutional — opened the doors of change. However, making sure that decision was translated into actual practice, especially in defiant ex-Confederate states, took a Herculean effort, with armed guards necessary to protect integrating students in the Little Rock school system in 1957. Nobody who opposed injustice against Black people had any illusions about the difficulties that lined the path to racial progress.

No more moving to the back of the bus

Relegated to the back of the bus in the colored-only section, it was against the law for African Americans to sit in the front white-only section. In the event of a full front section, a black person in the rear of the bus was required by law to stand so a white person could sit.

On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks decided against giving up her seat in the colored-only section to a white person. Tired after a long day in her seamstress job at a local department store, Rosa Parks repeatedly refused to get up as required. On that chilly December day, Mrs. Parks was eventually arrested, fined and jailed.

The Women’s Political Council, a grassroots organization of African-American women fighting for civil rights, learned about Mrs. Parks’ arrest. They circulated flyers calling for a boycott of the Montgomery, Alabama, bus system.

Word quickly spread through the African-American community, and on Dec. 5, 1955, 40,000 of the city’s black residents refused to ride any Montgomery city bus. That same day, African American leaders within the community joined together and created the Montgomery Improvement Association, with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as its president.

Paving the way for a better tomorrow for African Americans

The Montgomery bus boycott of 1955–56 heralded a new era in the fight for fairness and equality in the Jim Crow South, and ultimately inspired African Americans of all ages and backgrounds to assert their rights and privileges.

This notable event — and the amazing transformation in expectations it wrought — was not followed immediately by further bold action, but with grassroots organizing and reflective debates over the direction and future of this action-oriented rejection of the status quo.

In the wake of the Montgomery bus boycott and the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Council, the fight for better education took center stage in the struggle for civil rights below the Mason-Dixon line.

The sit-in campaigns that tackled segregation in public facilities would not begin in earnest for another five years, but following the Montgomery bus boycott, everyone in the African-American community — both North and South — realized a new day had arrived.

Meanwhile, in the North, civil rights activists embraced a more comprehensive, multi-faceted approach in their coordinated attacks against the barriers of legalized discrimination. Mass migrations from the rural South to the urban North, ongoing since the end of the Civil War, had altered the region’s racial landscape forever. Sizable enclaves of African Americans in northern states developed, where Black people could pool their talents, resources and desires in environments where the hair-trigger threat of immediate lethal violent retaliation for real or imagined slights was virtually eliminated (except arguably in encounters with the police).

Following the end of World War II (in which more than a million African Americans served in one form or another), black community leaders in Northern cities enjoyed an expanding population base and increasing enthusiasm among community residents. In a greater position of strength, they could, and did, push throughout the 1940s and 1950s for the rights of black people to participate equally in all aspects of society. Advocating persistently and without compromise, black communities called for an end to segregation in the school system, in housing, in public facilities, in the job market and eventually in marriage.

Despite the focus often placed on the struggles in the South, African Americans in the North faced the same obstacles to freedom. There, racial prejudice was only slightly less rampant and pervasive. We have been taught to associate the term “civil rights movement” almost exclusively with the actions of African Americans in the South, but the struggle for fairness and equality in the North actually preceded the more publicized Southern campaigns and, in general, reformers in the North focused on a wider variety of cultural, social, political and economic issues than their brethren in the former Confederate states.

In the South and nationally, the civil rights movement eventually progressed beyond the gradualist, legalistic approach that defined its earliest stages, and it was the example set by Northern civil rights activists that helped pave the way to a broader campaign for social justice. New York City, with the largest African-American population in the country following the great Southern migration, was a bastion of civil rights activism in the 15-year period from the end of World War II to the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960, when the attack on Jim Crow laws and other forms of outrageous discrimination in the South finally took off in earnest.

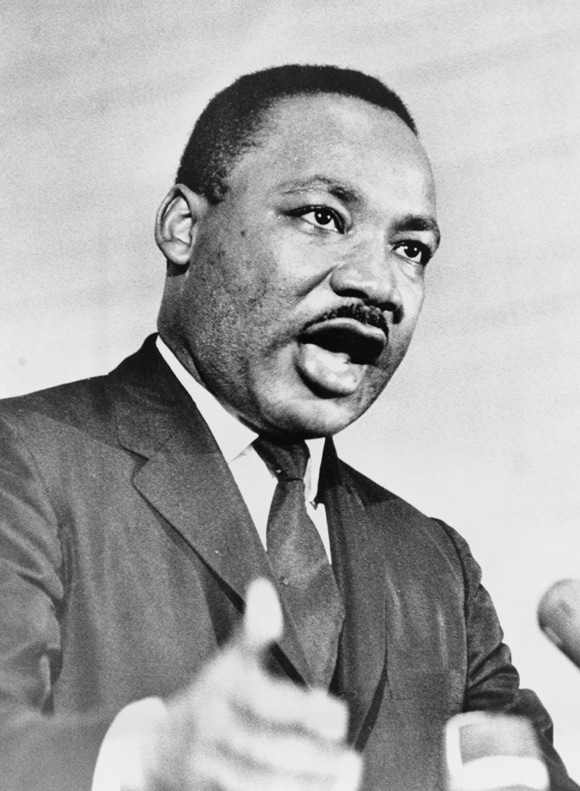

An icon of the movement: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Portrait of a hero: A leader emerges

Born on Jan. 15, 1928, to Baptist pastor Martin Luther King and his wife, Alberta, one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s early notable achievements was graduating from high school at the age of 15. He was ordained in his final semester of college and then went on to deepen his understanding of Christian liberal ideology at seminary. Although his start as a theologian was unexceptional, his aptitude for the subject matter resulted in an impressive academic profile. In his third year of school, he was elected class president — the only black student out of 11.

Dr. King earned his PhD in systematic theology from Boston University’s Seminary School in 1955. The year prior, King had taken on the mantle of two new roles — pastor at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and husband of Coretta Scott, a student at the New England Conservatory of Music, whom he’d met during his undergraduate days. In the same year he completed his doctoral studies, King was voted the president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, a group founded to protest the arrest of Rosa Parks for her civil disobedience. King was also named an executive committee member of the Montgomery NAACP chapter. During his time as an activist, King inspired people with his sermons and other writings, he led demonstrations and marches, and he suffered intimidation from the government and terrorism from the White population. He became an integral part of the civil rights movement.

Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, the day after giving one of his many uplifting sermons. In his less than 40 years on Earth, Dr. King became arguably one of the greatest leaders in world history.